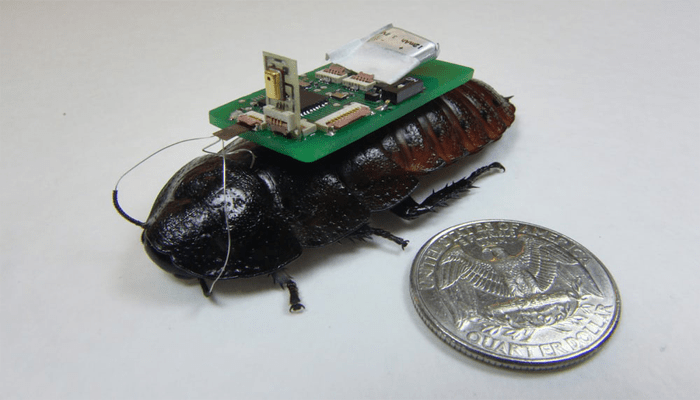

Robots don’t always need to be built from scratch. In the case of “biobots”, scientists have been able to hack into insect, turning them into remote-controlled scouts to gather data and map unfamiliar or unsafe areas. Researchers at North Carolina State University (NCSU) have already demonstrated the hardware and software that would make this possible, and have now thrown drones into the mix, to act as aerial beacons that guide and contain the biobots to areas of interest.

The NCSU biobots are made by fitting cockroaches with tiny electronics hooked up to their antennae and cerci, which the bugs naturally use to navigate. Located near the back of the abdomen, the cerci detect air movements and warn the critter of an approaching predator, while the antennae feel around in front for solid objects. Scientists can electrically stimulate these organs to effectively drive cockroaches remotely, using the cerci as an accelerator and the antennae to steer left and right.

Previous studies have suggested ways to map dynamic environments, such as collapsed buildings, using either autonomous or sound-sensitive biobots. The NCSU system would see bugs allowed to run freely around a small, designated area, with a UAV keeping watch from overhead. If a bug strays too far from the drone, their sensors will tell them there’s an object in the way, prompting the bugbot to turn back.

“The idea would be to release a swarm of sensor-equipped biobots – such as remotely controlled cockroaches – into a collapsed building or other dangerous, unmapped area,” says Edgar Lobaton, co-author of the study. “Using remote-control technology, we would restrict the movement of the biobots to a defined area. That area would be defined by proximity to a beacon on a UAV. For example, the biobots may be prevented from going more than 20 m (66 ft) from the UAV.”

As the bugs explore the environment, an algorithm processes the sensor data they gather to give observers the lay of the land. When enough data has been collected for a clear map of the area, the drone slowly flies over to an unmapped adjacent section, dragging the biobots with it to start over. The software can stitch the two maps together, and the process can repeat until the whole building has been explored, creating a map that first responders or other teams can use to navigate hazards or find survivors.

“We had previously developed proof-of-concept software that allowed us to map small areas with biobots, but this work allows us to map much larger areas and to stitch those maps together into a comprehensive overview,” says Lobaton. “It would be of much more practical use for helping to locate survivors after a disaster, finding a safe way to reach survivors, or for helping responders determine how structurally safe a building may be.”

To test the system, the researchers unleashed a swarm of “Hexbugs”, 1.5-in (3.8-cm) robots that mimic cockroach behavior, into a lab maze. A camera mounted overhead stood in for the UAV, and a cart moved obstacles across the maze to simulate the UAV moving to a new area. As the robots ran around the limited space, the software was able to paint a basic picture of the environment based on the areas they did and didn’t move through. While these tests were run with fully robotic bugs, the team says the next step is to see how biobots fare in the experiment.